Introduction

Space technologies as Remote Observation and civil space-based Earth Observation and its applications capabilities have become indispensable. Their crucial role in improving humankind's daily life could be evidenced in its importance to connect people via telecommunication satellites and to support their commercial transactions. In practice space technologies have been used by state and non-state actors to address various global matters and that could be manifested in the reliance on these means to achieve the 2030 "United Nations Sustainable Development Goals" (SDGs). Space technologies' crucial role in achieving the 2030 SDGs may be pinned in the 2030 "Sustainable Development Agenda", through the importance of the Earth Observation technologies (EO) and Geolocation satellite services (GSS)[1]. However, space-based technologies use to support the achievement of the SDGs is not limited to the EO and GSS; it includes more means like human and space flight and microgravity research and satellite communication technologies. The witnessed paradigm shift in space exploration gave rise to infinite possibilities led humankind to master the space harnessing for unprecedented socio-economic development. Consequently, the benefits of these technologies have been maximized to preserve the environment[2] response to disasters, protect biodiversity, enable education, manage the weather, provide Telemedicine services and manage agricultural activities[3]. Nonetheless, healthcare remains one of the most crucial subjects to be addressed due to its role in ensuring healthy communities and its impact due to its interconnection to all other spheres of humankind's life. Thus, amid the current Covid-19 (Coronavirus) outbreak, the compelling situation has put forward the crucial role of the space technologies, highlighting their use in disaster management, international cooperation and Telemedicine, which will be addressed in this article.

[1] UN General Assembly resolution, UNGA A/RES/70/1: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development September 25, 2015, paragraph 76, p 32. United Nations Website. <https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E.>

(Accessed on November 19, 2019).

[2] UN General Assembly resolution, UNGA A/RES/70/1: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development September 25, 2015, paragraph 76, p 32. United Nations Website. <https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E.>

(Accessed on November 19, 2019).

[3] Simonetta Di Pippo, The contribution of space for a more sustainable earth: leveraging space to achieve the sustainable development goals, Global Sustainability (GS) 2 (2019), 1-3, p1.

The use of satellite technologies in disaster management has been critical in timely allocating, assessing containing and mitigating the risk.

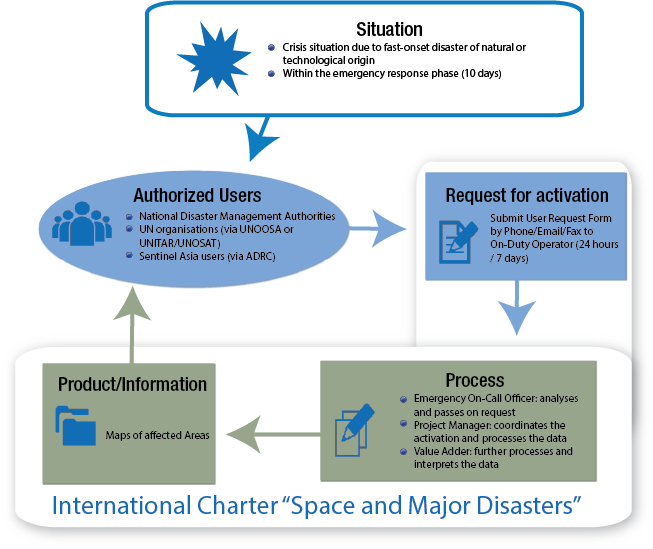

The first international framework on the application of satellite remote sensing in the management of disasters was agreed upon in 2000 under the “International Charter on Space and Major Disasters” (the Charter). The latter is an agreement under which international humanitarian collaboration is established to enable the free use of satellite data to rapidly respond to disasters[1]. The Charter is activated by an authorized user who is a competent authority acting on behalf of a country, which its space agency a member to the Charter. Authorized users are eligible to activate the Charter to manage a disaster within their countries or non-member countries. However, in order to ensure a timely action to manage the disaster, United Nations Office For Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), United Nations Institute for Training and Research’s UNOSAT are authorized on behalf of the United Nations Agencies, and Sentinel Asia’s users, to the activate the Charter upon large-scale disasters. Furthermore, since 2012, the Charter has adopted the international principle of Universal Access and consequently, the Charter was opened to any disaster management authority to become a member[2]. It is of importance to mention that the Charter can be activated only if the conditions are met. First, the disaster must be of a natural or technological origin, second the request must be made within ten days from the occurrence of the disaster. Thus, the compelling sudden event or situation, which may have a significant impact and consequences to the environment, lives and infrastructure is the primary condition of the Charter activation. Nevertheless, the temporal scope of the Charter is limited due to its mandate limitation, which dictates that the support under the Charter lasts from one to four weeks. [3]

Satellite technologies use under the Charter to mitigate disasters’ risks hinges on efficient and rapid responsive support. Once the request is notified, the Emergency team analyzes the situation to decide upon its eligibility for the action under the Charter. Whereas the request falls under the scope of the Charter, an immediate acquisition plan is made to process the satellite imagery and notify the harvested information from the satellite imagery to the disaster responders. Following the observation planning, users take the adequate satellite command and surveillance to monitor the disaster’s evolution in order to record the data and transmit it to the ground for analysis and quick report response. The members of the Charter may intervene to analyze the images to assist in the risk assessment[4]. The mechanism of disaster response to mitigate the risks that fall under the Charter may be summarized in the following chart.

Credit: UNOOSA.

UNOOSA, UN-Spider, Knowledge Portal, Space Based Information For Disaster Management and Emergency Response: The International Charter Space and Major Disasters, UNOOSA, 2019.

Since the efficiency of the Charter lies in the timely response to disasters, it is critical to identify the time frame to react under the designed process. As per Voigt et al. (2016), the average of overall satellite Emergency response time (from mobilization to the first product from 2000 to 2014) was reduced from 4.5 days in 2006 to 2.5 days in 2014 [5]. The efficiency and rapid response of a space agency’s satellite application to a disastrous situation may be demonstrated through JAXA satellites’ capabilities as an example. The JAXA’s “ALOS-2”, also known as “ALOS-2 Rapid Response” approval to an emergency observation request may be granted within the hour before the “command uplink”. Once the approval is granted, automated data analysis is made within the next two hours, and the provision of the information on the area of the disaster may be provided within five hours. ALOS-2 capabilities also encompass night observation rendering the emergency response more efficient since it is useful to manage the next day report[6]. Nonetheless, it is of importance to mention that the “International Charter on Space and Major Disasters” scope is not only covering environmental disasters as large scale oil spills and massive wildfires. Pandemic diseases management also falls under the scope of the Charter as it will be analyzed next.

[1] UNOOSA, UN-Spider, Knowledge Portal, Space Based Information For Disaster Management and Emergency Response: The International Charter Space and Major Disasters, UNOOSA, 2019. <http://www.un-spider.org/space-application/emergency-mechanisms/international-charter-space-and-major-disasters>. (Accessed on March 19, 2020).

[2] UNOOSA, UN-Spider, Knowledge Portal, Space Based Information For Disaster Management and Emergency Response: The International Charter Space and Major Disasters, UNOOSA, 2019. <http://www.un-spider.org/space-application/emergency-mechanisms/international-charter-space-and-major-disasters>. (Accessed on March 19, 2020).

[3] Courteille, Jean-Claude, International Charter for Space and Major Disasters Space and Major Disasters’ Space Based Information in Support of Relief Efforts After Major Disasters’, UNOOSA, 2015. <https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/pres/stsc2015/tech-56E.pdf>. (Accessed on March 19, 2020).

[4] UNOOSA, UN-Spider, Knowledge Portal, Space Based Information For Disaster Management and Emergency Response: The International Charter Space and Major Disasters, UNOOSA, 2019. <http://www.un-spider.org/space-application/emergency-mechanisms/international-charter-space-and-major-disasters>. (Accessed on March 19, 2020).

[5] Voigt, Stefan, Fabio Giulio-Tonolo, Josh Lyons, Jan Kučera, Brenda Jones, et al., Global Trends In Satellite-Based Emergency Mapping, Science Journal (SJ) 353:6296 (2016): 247–252.

[6] Kaku, Kazuya, Satellite remote sensing for disaster management support: A holistic and staged approach based on case studies in Sentinel Asia, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction (IJDRR) 33 (2019):417-432.

About the writer

Malak Trabelsi Loeb

Senior Legal Consultant